Search Posts

Recent Posts

- The Long Goodbye January 18, 2024

- Once More Around the Mulberry Bush January 9, 2024

- The Wash December 28, 2023

- The Truth About Carver Dogs December 1, 2021

- The Question of Pain November 9, 2021

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Champion

I recently saw a suggestion that dog people not refer to their Bulldogs as champions because it would draw the attention of humaniacs. I, myself, would advise to always assume that anything you put online in any form will be perused by humaniacs; however, should we avoid calling our dogs champions? After all, there are show champions and other types, too. I personally think it’s safe, but always assume that anything you put up will be scrutinized by those who may not have your best interests at heart. But where did the word champion come from anyway?

That originally was a term used for boxers, wrestlers, and sports teams, as it meant they were the best of a specific area. It could be of a city or a state or the world. They were the best in their category: boxing, wrestling, or a baseball team. (Yes, baseball was once more popular in America than football!)

Show dog people started using the term in a different way. It didn’t mean the dog was champion of a given area; it meant something else. Showing dogs for conformation was started by upland game hunters that wanted to have competitions in appearance for their dogs. But it was started in England in the 19th century, and the group governing it was called the Kennel Club. Some of the people who wanted to have a competition for their breeds that were not hunting dogs wanted to join and have the same competitions. It was for that reason the Kennel Club created groups. They had “Sporting Dogs†for their dogs and “Nonsporting†for all the other dogs. Later, they added other groups, such as “Hounds†and “Working Dogs,†but “Nonsporting†is still there, and ironically the show Bulldog is in that group. When other countries had clubs that wanted to do the same thing, they started Kennel Clubs, too, but they had to add the country to the name, such as the American Kennel Club.

But how did they determine a champion? It was done in a manner that did not denote that the dog was champion of a given area or place. The canine was granted a championship for winning a given number of show points, but three of the shows had to have minimum number of competitors. Otherwise, a dog could have terrible conformation, but could win points by being the only canine of its breed in a class in a series of shows of low attendance by that breed. A written standard defining the ideal physical traits of a breed was always made official, and individuals were judged by how close they came to matching the standard in every way. That’s why they’re called “conformation shows,†as the winning dogs are the ones which the judge thinks most conform to the standard.

But things got more complicated. Chauncey Bennett in the late 19th century started the United Kennel Club to register his favorite breed (ours), along with some other worthy breeds that were left out of the AKC. A show standard was drawn up, and a name was decided upon. That was American (Pit) Bull Terrier. I don’t know if the name “Bulldog†was ever considered, even though dog men commonly called them that. But there was the show Bulldog who already looked so different. They decided that our breed was the fighting version of the show Bull Terrier. The reason “pit†was in parentheses was that some dog men wanted only “American Bull Terrier,†while others wanted “Pit Bull Terrier.†Bennett was a diplomat, so he gave both options by including “pit†but having it optional, which was denoted by the parentheses. When Guy McCord started the American Dog Breeders Association in the early 20th century, he used the name “Pit Bull Terrier,†and no other breeds were accepted.

Although the UKC never got into showing dogs in those days, they did have a standard for each breed. At first, the UKC was a labor of love for Bennett, but it became profitable because a lot of breeds were registered that weren’t recognized by the AKC. He really hit gold with the coonhounds, as there were lots of those dogs kept throughout the country, but primarily in the South. A magazine was started, Bloodlines Journal, which featured our breed at the front, even though the coonhound people were certainly more numerous. Traditionally, pit dog men who didn’t sell dogs kept their own pedigrees, and they didn’t feel they needed to send in a record of their breedings, a lot of which they wanted secret anyway, for a registry to verify with papers. Nonetheless, Bennett kept true to his favorite breed, and he is the first one of which I am aware that came up with the idea of a pit champion. It was modeled along the line of show champions. A dog had to win three contract matches. The hitch was that the only matches that counted had to have UKC-registered dogs, and the referee had to be UKC-licensed.

In those days, it was a good idea for recognizing the accomplishments of a given dog, and it was perfectly safe, as there was no law that specifically outlawed the contesting of dogs. The only problem was that the people who hadn’t registered their dogs with the UKC weren’t eligible for the honor.

For that reason, there weren’t a lot of champions, just as there had not been before that time. Some very excellent dogs, such as Galvin’s Pup had multiple wins, and were never called “champions,†but that was way back in the 19th century. Even after the UKC came out with its championship system, there were very few dogs that gained that title. It was just too much to expect of a scattered and sparsely populated pit dog community to get UKC-certified referees for every match, let alone to make sure that all opponents were registered with the UKC.

It wasn’t until about the 70s that pit dog magazines began to recognize champions and even give out certificates. Until Jack Kelly’s Sporting Dog Journal, the longest running magazine was one that was started by I. Q. Kennedy back in the early 50s. It was called Pit Dogs, and it was later taken over by Pete Sparks. Sparks worked for the government in a reproduction facility, and Pete could use that for printing the magazine, along with government paper. You can be sure the humaniacs were downright apoplectic when they learned that! Although dog men—including myself—loved the periodical, it probably did more harm than good. It drew a lot of unwanted attention to the pit dog game, as he printed pictures of dogs in action. The general public doesn’t know what they are seeing when they view such things, so it inflames them to see the dogs “being abused.†In any case, the magazine never awarded championships. Sparks later changed the name from Pit Dogs to Your Friend and Mine, but that did little help to quell the use that the humaniacs were making of the magazine with all its “gruesome†pictures.

There were many pit dog magazines before that, including Dog Fancy and Pit and Pal. A lot of those were quite good publications, as Bob Hemphill edited the latter, but none of them offered championships or lasted quite as long as Your Friend and Mine or Sporting Dog Journal.

There were a couple of magazines, including one short-lived one put out by Don Mayfield and another one edited by Raymond Holt that offered pit championships that were modeled along the lines of the UKC rules, but they didn’t require UKC-licensed referees or for the dogs to be so registered. Holt attended Going Light Barney’s last match. It went almost two hours, with Barney going against an exceptionally good dog, and Holt was so impressed that he gave Barney the first Grand Championship title. Barney had won eight matches, but he lost his third when he was counted out in Texas. There were considerable questions and suspicions about that match, but the point is that he had lost a contest.

When Sporting Dog Journal came out with its champions, it took a while before a Grand Champion title was ever awarded. Eventually, it was decided that a Grand Champion not only had to have won five matches, but it could not have lost even one—no matter how gamely that may have been. Under those rules, the original Grand Champion (Barney) would not qualify for that title.

Titles mean something, but not everything. Some very influential dogs only won one match. Two examples spring to mind. The first would be Tombstone, who beat a dog considered the best in the country, and he made one of the gamest scratches ever seen. The other would be Bolio. Again, it would be the case of the quality of the dog he won over. His opponent had absolutely destroyed his opposition before, but Bolio was a magician in staying out of trouble and finally defeating his much-heralded opponent.

In my mind, though, the word “champion†should apply to all good dogs. They are incredible animals – and I just can’t think of any that deserve it more. Galvin’s Pup, I hereby anoint you a Champion, nearly a hundred and fifty years after your reign!

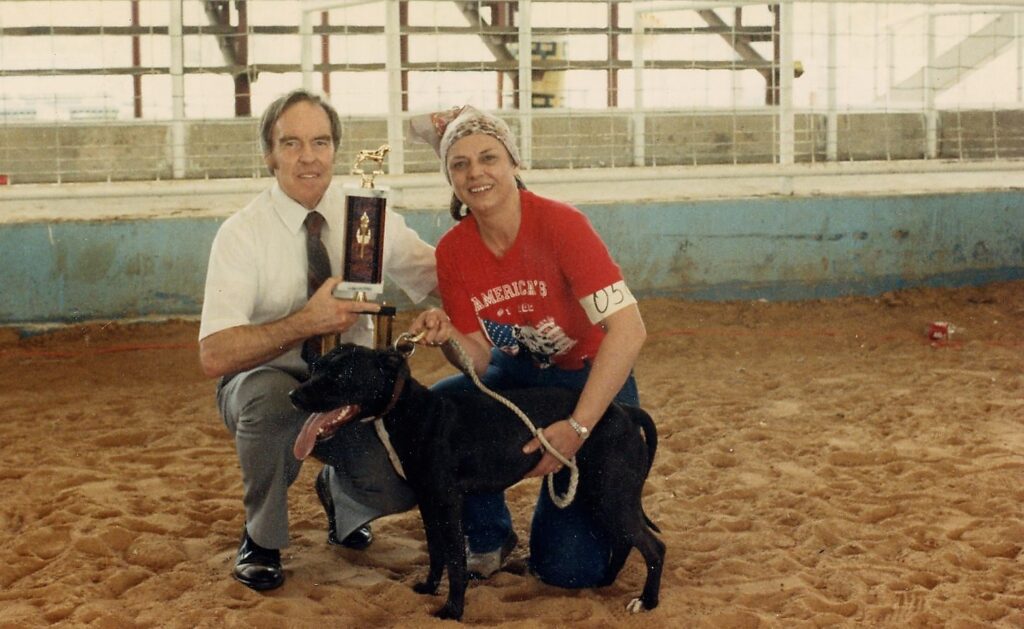

Champion is a word that I think fits many members of our breed, not just pit artists. And there are many individuals that have earned the title in other ways, including show dogs, as well as weight pullers, agility dogs, obedience drills, and many other competitions. So many of our dogs are simply great dogs, and they don’t need titles for us to appreciate them. And I think that, in itself, is simply champion!

I don’t see a thing wrong with it Richard very nice and it they used it it may very well sell more rags for them I recently heard about an advance judge who can no longer judge advance shows because he is a felon crazy world we are living in keep up the great work

Your friend

Kevin squires

Thanks, Kevin, and you are an old friend. I am understanding that they have to be very careful, but I’m not very PC!

This is a fantastic piece! I really enjoyed reading it please keep up the great work on the history of this breed.

Thanks.

Thanks/