Search Posts

Recent Posts

- The Long Goodbye January 18, 2024

- Once More Around the Mulberry Bush January 9, 2024

- The Wash December 28, 2023

- The Truth About Carver Dogs December 1, 2021

- The Question of Pain November 9, 2021

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

A Rose by Any Other Name

Does it make any difference what the American Pit Bull Terrier breed is called? After all, it is still the same breed regardless of its designation, right? As Juliet said in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.†She is speaking to Romeo about the artificiality of names and human conventions, and I agree.

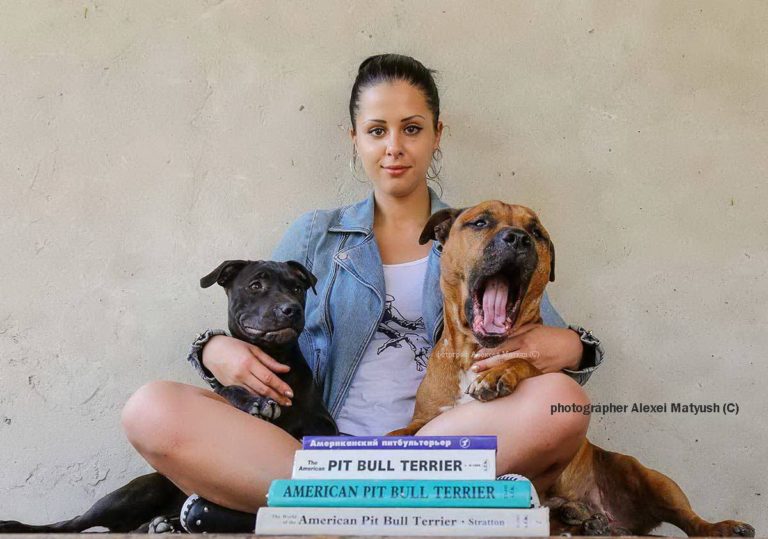

However, in the case of our breed name, we need continuity, so I am in favor of retaining the name. That is in spite of the fact that I don’t consider our breed a Bull Terrier at all. Since my books on the breed were the first ones written in several decades, they were quite popular and widely read—around the world, in fact—and one was translated into German. I know from experience that they were translated unofficially into other languages, too, as I saw Italian translations in Italy and other translations in other countries.

Now, the English editions are out of print, and it was not for lack of sales. The Michael Vick situation caused a media frenzy that resulted in the discontinuing of my four publications on the breed.

This concerns me for two reasons. First, with few exceptions, the books on the breed that are still being published are downright laughable. They either misinform or they give very little information. And they nearly all contend that the APBT originated with a cross between the original Bulldog and a terrier. (Usually, the English White Terrier is specified, one that is extinct.) Such authors are ignorant of my books or deliberately ignored them.

I would never demand that people agree with me, but a lot of scholarship went into those books. Did the writers think that I had never read the 19th century books that referred to the history of the Bull Terrier? I referred in my books to examining Colonel Barnes very excellent library of original editions. Not only did I pore over such material, but I also examined art work, dating back five hundred years. And guess what I found? There were dogs then that very much resembled the modern APBT. There were also Greyhound-looking dogs and trail hounds. Obviously, the people of Shakespeare’s time were certainly not ignorant in all things. They had learned to keep specialist breeds pure from random breeding. Their very existence demonstrated that selective breeding was already taking place.

I should mention parenthetically here that we are only dimly aware of true history. After all, we don’t even get the straight scoop on modern events. It has always been that way, in my experience. Anything that I was ever connected with that was newsworthy got distorted, sometimes beyond recognition, by newspapers. On important stories, newspapers struggled mightily to get things right, as they didn’t want to be scooped or exposed by rival newspapers. It is for that reason that I am not happy about the apparent imminent demise of newspapers. It is a process that has been going on a long time, but I am most concerned about independent, muckraking papers. These are the ones that used to dig deep and keep governments and businesses honest. At least, that was the trend. A consolidation of media ownership has been going on for many decades, and that really compromised accurate reporting.

Unfortunately, most people get their news from television—and the TV sources are far worse than the newspapers ever were! For that reason, I take everything with a grain of salt until all the facts are in. Unfortunately, there are times that they don’t all get in.

If we can’t even know much about modern happenings, how can we be sure about history? The answer, of course, is that we can’t—but history is fascinating just because we have to ferret out the facts and can never be sure about them! When I get my time machine perfected, I’ll be able to answer more questions with greater confidence.

Consider that the great composer Ludwig van Beethoven has not been dead for even two hundred years yet (that will be in 2027). Also, contemporary musicians who were reasonably close to the composer wrote biographies on him. In addition, since Beethoven was nearly stone deaf in the latter part of his life, there are numerous “conversation books.†These were notebooks upon which visitors wrote questions and comments to Beethoven. There are museums here and in Germany and Austria that contain many artifacts that Beethoven actually used. Even with all of this, there is much dispute about certain details of his life. There are many gaps.

Now, let us go back to Elizabethan times, the time of the original Queen Elizabeth and of Shakespeare. There have probably been more books written about Shakespeare than any other person. Yet, little is known.

Once we get back beyond a thousand years, we can’t even tell mythical personages from historical ones, although assumptions are made. Did Socrates really exist or was he just a character in Plato’s stories? For that matter, did Plato exist as a historical person? Probably, but we don’t really know.

In any case, I hope that I’ve made my point that human history is really shaky, even though it may be fascinating. And that’s with what were considered the important things. Dogs were not much written about. Take it from someone who has pored over countless ancient texts, trying to find references to dogs and dog breeds.

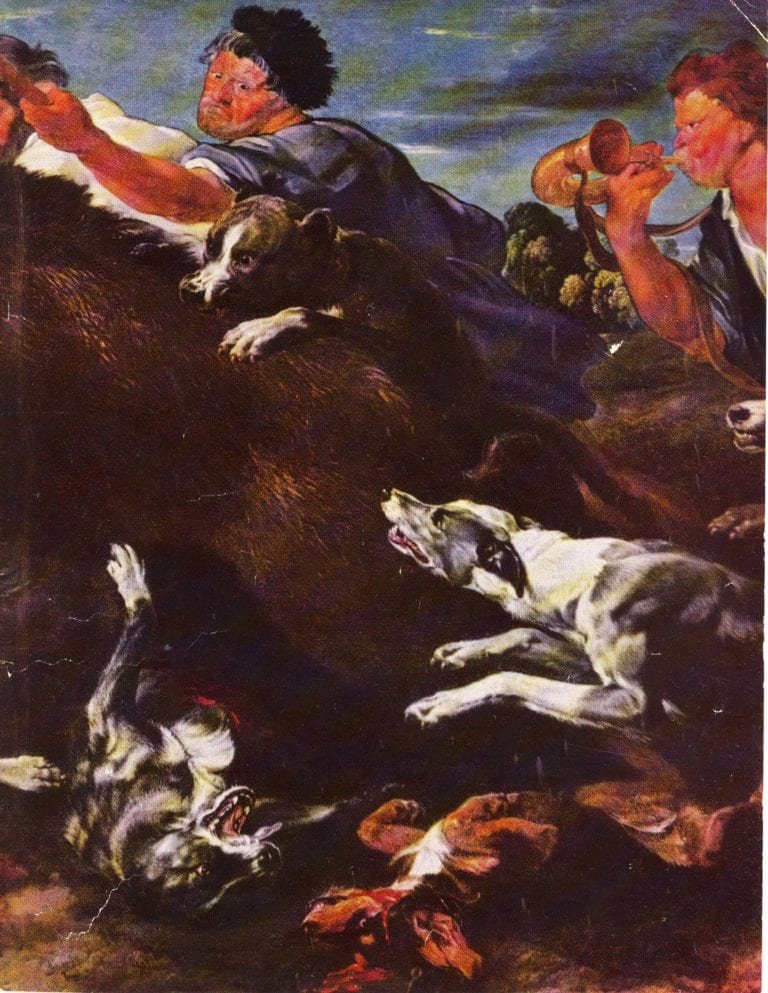

Artistic depictions are about as close as we can get to a time machine. We assume that what artists painted were things that the artist actually saw. Of course, we have to be careful, as portraits of satyrs and unicorns were plentiful! But if paintings done 500 years ago actually showed our dogs looking very much as they do now and performing the types of things (catch work, hunting, fighting) that they are known for now, then it is logical to assume that these were likely progenitors of our breed.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term “Bulldog†first appeared as “bold dogge†and talks of the dog’s use as a catch dog for a butcher. Now, did this mean “bold dog†or “bull dog� We can’t know for sure, but if the dogs would actually seize a bull by the nose for the butcher to secure, they must have seemed bold indeed as compared to other dogs.

But the main point is that if the breed was already the same in appearance, there was no need for the supposed cross with a terrier. Another point worth mentioning here is that the term “terrier†was never defined. The term usually referred to small dogs that were used on varmints as opposed to hounds that were used in the hunt. The Bulldog was sometimes referred to as a hound, and why not? It was useful in the hunt of wild boar and other rough game. However, only royalty and landed gentry could own hounds. Peasants weren’t supposed to hunt. They were allowed terriers however. Could they have called small Bulldogs “terriers†just so they would not be subject to harsh penalties—or even death?

Another fact to throw in to the mill here is that there is evidence of the APBT having been in this country long before the putative Bulldog x terrier cross. There is evidence in artwork, and William J. Lightner once told me that his father had started the Lightner strain with his uncle before the Civil War. I was always curious about why the breed was called “Bulldog†in informal conversation. According to several dog men whose birthdays went back past the turn of the 19th Century (like Frank Fitzwater), that was always the case—with one exception. The Irish tended to refer to the dogs as “Pit Terriers.†And their dogs were especially small. Could the name have developed from the olden days when peasants could not keep “hounds†such as the Bulldog? I don’t know, but it’s worth thinking about.

So how did the present name for the breed develop? When dog men such as Armitage wrote books about the breed, they used the term “Bull Terrier†for the breed. To distinguish the breed from the show Bull Terrier, they often added the word “pit,†and “Pit Bull Terrier†is still used for the breed today, although not very prevalently. When Chauncey Bennett founded the United Kennel Club in 1898, he called the breed the American Bull Terrier. Many fanciers wanted the term “pit†retained, so he kept it in the name, but placed it in parentheses. The ADBA first registered the breed as “Pit Bull Terriers,†way back in 1909, but eventually adopted the “American†part of the title. Interestingly, I discovered through Louis B. Colby that the American Kennel Club also registered the breed as “Pit Bull Terriers†in the early part of the last century.

It is worth noting that a lot of the diehard pit dog men were in favor of leaving the “pit†out of the name. Bob Hemphill was one of those in favor of the name “American Bull Terrier.†Even so, the name is a total misnomer. The breed is not of American origin, and it is my belief that it is not a Bull Terrier—and I suspect it was Hemphill’s, too, but I never discussed it with him. The name “American†helped promote a breed, and I think Bennett felt that the American version was different from other countries. That idea was falsified by the very fact that Irish and English importations were coming in at that very time. But Bennett’s heart was in the right place. He used the name “Columbian Collie†to promote the white Collie. (Columbia is a synonym for America, and it was once a more common term than it is now.)

When the breed was being pushed (by Colby’s widow, among others) for American Kennel Club recognition (again!), the Bull Terrier people campaigned against the use of American Bull Terrier. Eventually, the name Staffordshire Terrier was adopted for use in that registry. Will Judy, the editor of Dog World, suggested the name “Yankee Terrier,†but it was never used.

In the late 50s, Staffordshire Bull Terriers were being imported into the country, and there was much heated debate about whether crosses between them and the Staffordshire Terriers in this country could be recognized as purebred Stafs. Howard Hadley was influential in preventing this from happening. Hence, the Staffordshire Terrier was renamed “American Staffordshire Terrier,†and the Staffordshire Bull Terrier was recognized as a different breed. Please note here that the show Bulldog, the Staffordshire Bull Terrier, and the American Staffordshire Terrier (not to mention the APBT) all came from the same basic stock. It was selective breeding that made them different.

I am well aware that I can’t expect the average reader to take the same interest in breed history as I do, but I would be interested in comments and questions. I should make the point here that I was not the first one to come up with the idea that our breed was the best representative of the old Bulldog. There were others before me. But I was the first one to research it thoroughly and to publish the results. Nevertheless, I have learned the important lesson: to live with ambiguity. I don’t have any special love for the breed history I have proposed. It honestly makes the most sense from all the evidence available. The one compelling thing to me is that it is a demonstration that our breed is an old and noble one that has endured hard times before. But once I get that time machine perfected, I’ll be able to speak with more authority!

In the meantime, I’d be interested in hearing from people who have contradictory evidence. I’ll answer questions if I am able. Obviously, this subject is much too complicated to include all the details in a single article.

In the article written by David Hancock, he asks is the Staffordshire Bull Terrier the original Bulldog. Ref: https://www.davidhancockondogs.com/archives/archive_790_899/829.html

He states:

“ The renowned Victorian dog-dealer and Bulldog breeder Bill George imported some Spanish Bulldogs and used them in his breeding plans. All these dogs were strong-headed but none were flat-faced. Muzzle-less Bulldogs were a show ring imposition and with such a handicap could never have seized and held a bull.”

He discusses the physical features necessary to bite and hold an enraged Bull:

“ The construction of the jaws of all the bull terrier breeds, from the misjudged Pit Bull to the American Staffordshire Terrier and our own Bull Terrier, show a wide mouth and an even bite, with strong development in the masseter muscle. They display a balanced muzzle, showing width and length. Our pedigree Bulldogs have restricted breathing and no means of gripping with strength.”

Mike Homan writes in his book, THE STAFFORDSHIRE BULL TERRIER IN HISTORY AND SPORT that in 1575 Abraham Fleming translated a treatise from Latin under the title OF ENGLISCHE DOGGES. For the mastiffs he says of the uses thereof:

“Serviceable against the foxes and badger… to drive wild and tame swine… and to bait and take the bull.”

He also states:

“May 30th 1599… the French Ambassador arrived here… The Queen did act this with the French Lords, to whom she made gifts more than splendid… diverse dogs mastiffs GREAT AND SMALL, hounds and setters, a quantity of every sort.”

I have also read that contemporary authors regarded the Bulldog as “a diminutive mastiff.”

I’ve seen Spanish Fighting Bulls and they are exceptionally quick on their feet – like a rhinoceros. It would take one exceptionally agile dog to escape the horns. Yet Spanish Bulldogs regularly baited the Bulls (that were originally from France, btw). These Bulldogs were described as “larger than the English Bulldogs”. But they are depicted as catchweight Pit Bulldogs (we call gamebred Pit Bulls “Bulldogs” here in South Louisiana; always have) such as Southern Kennels Champion May Day. They look to have been about 65 to maybe 85 lbs. which seems to match what was written about them in England.

We forget that Spain was a mighty power and they had the three strains of Alaunt and they spread them all over the world prior to England dominating Europe. It’s my theory that the so-called English Bulldog is likely Spanish.

We do see the first time the word “Bulldog” is recorded in England:

The first reference to the word “Bulldog” is dated 1631 or 1632 in a letter by a man named Preswick Eaton where he writes: “procuer mee two good Bulldogs, and let them be sent by ye first shipp”.

But as early as 1174 William Fitzstephen in his DESCRIPTO LONDONIAS mentions baiting both Bull and Bear among the established pastimes of Londoners in winter.

I say all of this to suggest Our Dogs are indeed older than we may know and he existed “everywhere at once” meaning the TYPE of dog did not exist in any one country.

We have the Bullenbeiser and Barenbeiser of Germany, too.

Did they all come from the Spanish? Quite possibly. Who knows for sure.

That crosses with all sorts of dogs with Our Dogs well established I do not believe that Our Dogs lacked agility (Bull-baiting, Bear-baiting and Lion-baiting). We do know that what is now called the Staffordshire Bull Terrier was a Badger-baiting dog according to Mike Homan’s research. My question is was it a Bulldog-Terrier cross? Terrier may have been blended in to get the dogs that size. That I will concede.

In 1835 animal baiting was banned and the original or Victorian Baiting Bulldog’s days were numbered. The bloodsport s continued but it moved underground in pubs where dogfighting, badger-baiting and the occasional monkey v dog occurred. It’s quite possible that crosses were made and blended to various “recipes” to have small, game dogs for sport.

I can imagine that.

But Bulldogs were already at this time in what is the USA and Central America. The Spanish conquered the southeast and southwest USA and they brought “mastinos” (mastiffs) and “lebrels” (strong-beaded Greyhounds) and “Irish Wolfdogs” to subdue the natives.

Here in Louisiana we have remnants of those dogs as Louisiana was once known as the “Florida Parishes”. The Cuban Bloodhound was also imported (and crossed) to hunt bear and cougar. It’s remnants were called “Brindle Bulls” here.

In summary, we know:

(1) Bulldogs were selectively bred from smaller, more active mastiffs

(2) Mastiffs may well be one of the heavier variants of the Alaunt which Chaucer says “were as large as a steer”.

(3) Crosses with gritty terriers DID take place

(4) Bulldogs came from various sources and they all did the same things – attack any animal it was asked to grab and work its hold until death was certain if allowed.

I just cannot imagine allowing such a Warrior

Race of dogs to be diminished. And I don’t think it was.

We have the small, thin-headed, obviously Bull and Terrier dogs imported in the early 1800s, followed by the round headed, short muzzled Bull and Terrier dogs then we have dogs that are larger and look just like our dogs today.

It’s my belief that we got heavy terrier cross, the fancier Bulldog crossed with terrier and finally the “real McCoy” which may have some of the more successful Bull-Terrier blood carefully blended back into the original Bulldog. What worked was bred. What did not was culled.

They are and always will be Bulldogs to me.

Sorry to be so long-winded.

I have gone through all the literature a long time ago, from the 19th century onward. A lot of it simply doesn’ jibe with the other evidence.